what solarpunk is, isn’t and why it matters

By Alex Holland with contributions from Alastair Ball and visuals by Claire Alexis.

“We shouldn’t attempt to define solarpunk, but what I can say is it’s definitely not what he says it is. What he is describing is eco-fascism.” – Reddit commenter

Newcomers to solarpunk are often drawn to what they hear is a sunnier depiction of the future. An inspiring change to the dominance of dystopian sci-fi we've seen in recent decades.

As they dig deeper they find communities of people joyfully embracing the possibility of more desirable futures. Yet they are also likely to come across the type of comments above.

The biggest and most active solarpunk group on Reddit - r/solarpunk

Chris Yak’s podcast “Solarpunk” has his future daughter writing letters to him from a Mars colonised by Elon Musk. While Kiesha Howard, who did the first TED Talk on solarpunk, has said that’s the last place she’d want to go.

Is only one of them solarpunk and the other a gaslighter? What about the variety of people calling themselves solarpunk who are for and against things like crypto?

WHY ARE WE DOING THIS?

To answer these questions, we have to ask “why solarpunk?” What’s it for? Is it just an aesthetic to fantasise about, or is it something more?

Straight outta solarpunk [IMAGE: By Cienias, City of Compton CGSociety contest entry]

At SolarPunk Stories we believe the greatest promise of solarpunk is to inspire radical change.

Providing inspiration for action has never been more important, nor urgent. The longer we delay the move to a sustainable and socially just world, the harder it’ll be to prevent nightmarishly bad climate breakdown.

One of the most visceral depictions of a climate broken world is The Road [IMAGE: The Road]

On a brighter note, however, it’s still possible to build a world that will be massively better for all life, human and otherwise.

Amen to this [IMAGE: Joel Pett for USA Today]

Solarpunk has the potential to inspire the collective action we need, which is why we want it to reach more people, more quickly. We want enough people to get excited and act to make a deliciously sustainable world a reality.

This is why we think that a lot of the energy that’s currently spent with different people trying to claim they’re the one and only ‘real solarpunk’ is a waste. We want people to start ‘agreeing to disagree’ with others so we might build our movement as a whole.

Local sustainability projects from grassroots green group Transition Town Brixton [IMAGE: TTB Projects]

In that case you might wonder, do we think there’s any use in defining solarpunk at all?

NOT TO DEFINE

We’ve attended a number of solarpunk events that have opened with speakers saying: “We cannot define what solarpunk is.” This is normally before they go on to promptly denounce someone else’s interpretation of it.

A search of #solarpunk on Instagram has brought up images as varied as dragons, a spaceship that looks like it’s parked on Tatooine, and someone selling what they claim is a ‘real hoverboard’ dressed as Doc Brown.

Are Game of Thrones, Star Wars or Back to the Future solarpunk? In that case what’s different about it? What would a newcomer to our movement make of this?

Confused definitions are coming [IMAGE: Game of Thrones]

If something can mean everything it effectively means nothing. This is why we think we should accept a variety of shades of solarpunk at the same time as attempting a definition of what our genre is and isn’t.

LAYERS OF DEFINITION

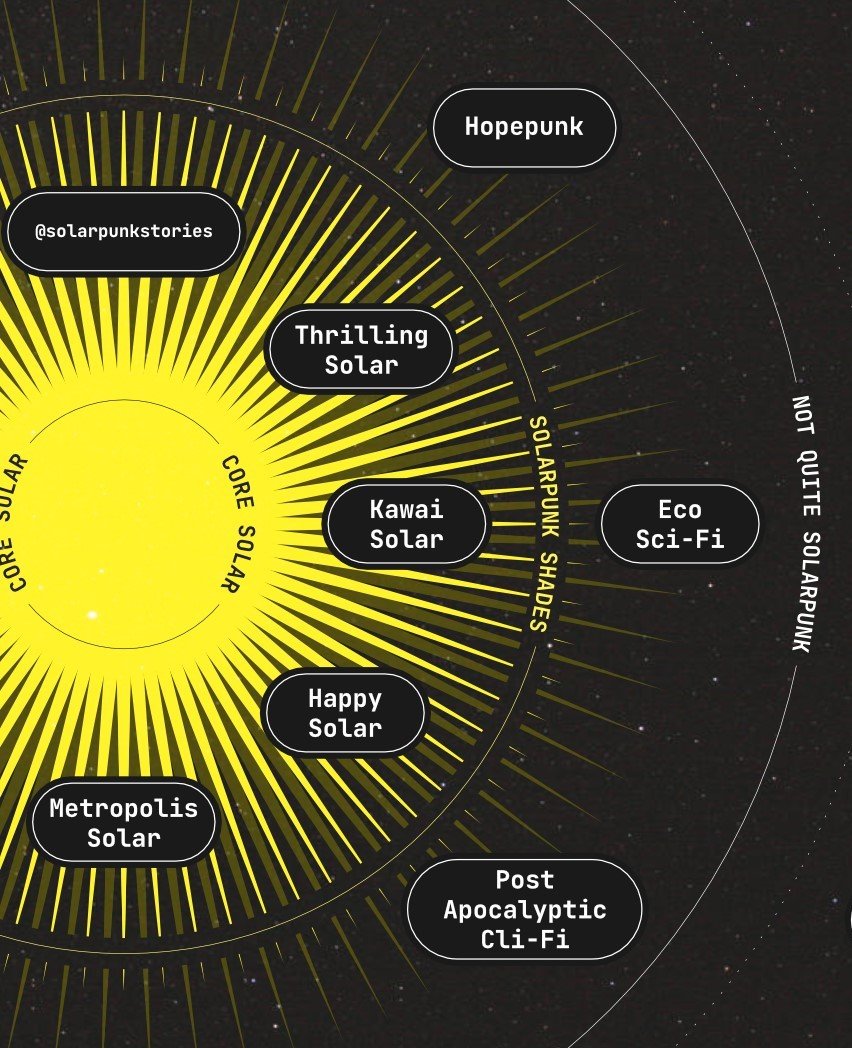

What we propose is that the definition of solarpunk might look like the sun sitting in space.

There’s the core of our star - what all solarpunk shades have in common.

An outer layer of this sun where different shades of solarpunk sit.

The icy darkness of the void which things that are not solarpunk are found floating in.

A fuzzy border lies between what the fully cold non-solarpunk is and the still warm shades are.

Our shades of solarpunk star [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

CORE SOLAR

For us, all shades of solarpunk share three main aspects in common.

It shows sustainable worlds that are not only possible, but desirable. These are visions of the future we could get excited about living in, not nightmares to avoid. Perspectives on what a sustainable future might look like vary widely and are one of the things that can separate the shades (more below).

It’s more socially just. Again, what people interpret this as varies widely. Broadly speaking, it depicts more equal, fair and inclusive worlds than the one we live in now.

It inspires action. We hope solarpunk art, stories, and activism will encourage more people to get moving to make these better futures a reality.

THE SHADES

Many shades of solarpunk [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

For us, the main types of solarpunk are different when it comes to visual aesthetics or written stories.

VISUAL AESTHETIC

KAWAII SOLAR

This shade has a children’s anime or cartoon-like style to it. These images tend not to have too much darkness or grime lingering in their corners.

They also tend to be more on the fantasy side of solarpunk, not depicting existing places that have been reimagined but ones drawn purely from the mind of the artist.

Are you an otaku for this shade? [IMAGE: Munashichi Future Economic View of Innocence 2015]

This can sometimes be called ‘Miyazaki core’, after Hayao Miyazaki, whose visual style is an inspiration for some examples of this shade. For more on whether we think Miyazaki’s actual films are really solarpunk or not see below.

More than just a yoghurt advert [IMAGE The Line Dear Alice Chobani Commercial]

METROPOLIS SOLAR

This shade tends to feature a lot of skyscrapers and flying cars. In many ways it’s like an update of Fritz Lang’s vision of the future in Metropolis.

Sky high solarpunk [IMAGE: Gal Barkan the Valley]

The buildings vary in their degrees of shininess from spotless glass supertowers, to those decorated with living green.

This is one of the shades least likely to feature any signs of pre-existing architecture from previous eras. It’s normally rendered on a massive scale. Because of this, if people are seen at all they tend to be only tiny figures in a much larger landscape.

Far out solarpunk [IMAGE: Solarpunk by Steven Wong]

This shade is often attacked by its critics as being “eco-futurist”.

COTTAGE SOLAR

This tends to depict small-scale rural communities in green settings. These can be wicker-weaved yurts, earth sheltered hobbit-style dwellings or old rural houses that have been adapted to be more green.

Wicker world [IMAGE: Luc Schuiten Jardin Saline]

This is sometimes derided by its opponents as not really solarpunk, but more ‘cottage core’.

ROOTED SOLAR

This shade tends to show places that look much more lived-in and could be created in the nearer future using existing technology and resources. It has few (if any) skyscrapers or flying cars. It’s often, but not exclusively, set in urban locations. It’s much more likely to show a real-world place that’s been solarpunked than Metropolis Solar.

London Calling [IMAGE: WATG Architects Fleet Street London]

Some versions of this shade can border on the more post-apocalyptic, cli-fi style. This is when they show future communities living in the partially decayed leftovers of our current world.

We feel this shade lives up more to the idea in Adam Flynn’s Solarpunk: Notes Towards a Manifesto when he wrote, “Solarpunk is a future with a human face and dirt behind its ears.”

Barrio solarpunk [IMAGE: Turf War by Arturo Gutierrez]

NOW SOLAR

This shade is more about people solarpunking it now by doing things like local food growing, and jugaad style fixes to make their communities more sustainable. These can range from low-tech guerrilla gardening, to the latest innovations in solar and other renewable technology.

Solarpunking it now [IMAGE: Kyoto shop]

MERGING SHADES

One shade or many? [IMAGE: The Line Dear Alice Chobani Commercial]

Many of these visual shades are not mutually exclusive and can be blended. You can see this in the Chobani commercial, which has the farmers living in a Cottage Solar style community which overlooks a Metropolis Solar looking city, or even the cover of our very own Solarpunk Detective Episode One.

STORY SHADES

For us solarpunk is as much a setting where stories happen as it is a style of writing in itself. Sci-fi genres have often been where love or war stories and thrillers have taken place.

Big Brother watches them getting it on [IMAGE: 1984 by George Orwell]

Think of how the love story in 1984 helps us identify with Winston Smith as the dystopian horrors of his world are revealed to us. Or how the war in Starship Troopers helped Verhoeven sell a satire on militarism to a mainstream Hollywood audience.

Beverly Hills 90210 beauties face off against killer alien bugs in Verhoeven’s classic Starship Troopers [IMAGE: Starship Troopers]

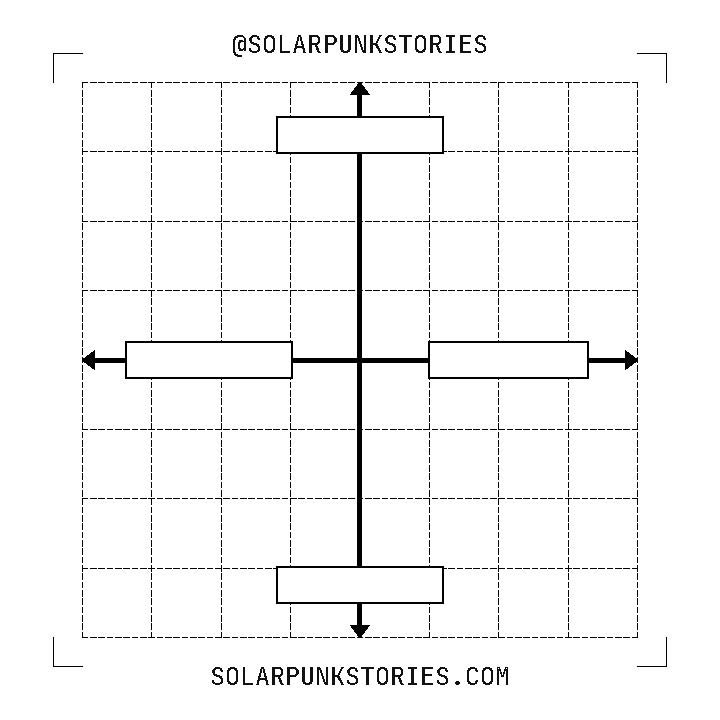

When it comes to thinking of shades of written storytelling for Solarpunk it’s the same. The main difference between tales is not so much their subtheme but their style. In particular where they lie on the axes shown in the diagram below.

As we see it, one of the main arcs are from those stories that go from being more thrilling to happier, and from being more fantastical to more rooted.

Where’s your shade? [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

There are other lines we could position stories on from being more technophiliac to tech-sceptical, urban to rural. For the sake of space in this piece, and to encourage you to come up with your own, we’re keeping it to these two here.

FANTASTICAL TO ROOTED

If a story has things like genetically engineered creatures and interstellar travel in it then it’s on the more fantastical end of the spectrum.

Things get extra terrestrial in this image often associated with solarpunk

Rooted Solar stories are ones that it is easier to envisage happening closer to now. The technology in them isn’t so outlandish and their future histories are easier to trace to the world we currently live in.

It’s Brooklyn Jim but not as we know it [IMAGE: Crown Heights Bodega EcoHaven Olalekan Jeyifous MOMA Exhibition]

One example of more Fantastical Solar would be The Spider and the Stars by D.K. Mok in SolarPunk Summers. This story has CRISPR-created pet spiders the size of labradors and tree-filled space stations.

At the other end of the spectrum would be a tale by friends of SolarPunk Stories, Commando Jugendstil - A Midsummer Night’s Heist, also in SolarPunk Summers.

IMAGE: Commando Jugendstil

It has their group doing a guerrilla gardening takeover of one of the main squares in Milan. The level of tech here is mobile phones and seeds rather than gene editors and space ships.

Their story is so rooted it could be set today.

HAPPY SOLAR

These types of stories have either no conflict, or very low levels of it, and no violence.

Whatever struggle exists tends to be more about things like arguments between friends, unrequited love or struggles about how to best implement localised energy systems.

Shiny happy people solarpunking around [IMAGE: The Fifth Sacred Thing by Jessica Perlstein]

You might imagine this narrative shade best matches Metropolis Solar. However these stories tend to be set more in self-sustaining rural co-operative style communities.

Some other examples include:

CAUGHT ROOT by Julia K. Patt - Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers

Where Giants Will Stand by Spencer R. Scott - XR Storytelling Showcase

THRILLING SOLAR

Murders are rare in solarpunked London 2066, but when they happen you call… [IMAGE: SolarPunk Detective #1 George Grey for SolarPunk Stories]

These are stories that show an essentially better world, yet one where conflict, violence, and murder still exist, though these aspects of life tend to be much lower than in our current society.

Many of the stories in the original Brazilian anthology that really popularised the idea of solarpunk back in 2012 were like this. These included not just conflict between characters but also murder, riots and even cannibals.

Solarpunk’s genesis, born in Brazil [IMAGE: Solarpunk Ecological and Fantastical Stories in a Sustainable World Published in the UK by WorldWeaver Press]

Other examples include:

AND MORE

There could be many other shades depending on how far down you want to specialise. For us, these are the main ones. You might think differently, if so we hope you’ll share your shades.

ON THE BORDER BUT NOT SOLARPUNK

The SolarPunk Stories sun [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

POST APOCALYPTIC CLI-FI

There are a number of stories we think could be fairly called solarpunk that are set in futures that are very close to, but not quite, post-apocalyptic cli-fi.

There are some where climate shocks have meant that major cities have been largely abandoned. In these worlds people are living in small ‘off-grid’ communities.

We think there is a key difference between these and the more hardcore post-apocalypses or disaster porn of harsher cli-fi. This is based on whether or not the stories depict places that are still desirable to live in.

Trickle down economics to the max [IMAGE: The wretched of the citadel from Mad Max: Fury Road]

When the vibe of the story becomes more “look what ruin we have wrought on the world and now we have to live in this wasteland” it tips it into post-apocalyptic for us.

There is a similar point when it comes to visual aesthetics. There are some images of the future identified as solarpunk which show a lot of decay and even abandonment of old infrastructure and places.

What makes imagery like these have a fair claim to being solarpunk is whether the people depicted living in these places seem to have built something new and more hopeful out of the decay of the old.

Like the image above by Aerroscape. The bridge may be submerged but the addition of the turbines, solar PV, roof gardens and sailing ships help this to feel less like Mad Max and more making the best of things.

SUSTAINABLE BUT NOT MORE SOCIALLY JUST

There are visions of the future which imply that they are greener than how we are living now but not more socially just.

In Gattaca, our gene-discriminated hero is unable to fully see the beauty of dawn over the vast fields of future Los Angeles solar panels.

Discriminating beauty in Gattaca [IMAGE: Gattaca Solar Fields]

Another is Cyberpunk canon Blade Runner 2049. This shows a desert covered in solar collectors and walls built to keep sea level rise from deluging a different future LA.

Solar but not our kind of punk [IMAGE: Blade Runner 2049]

Even some less dystopian films like Geostorm appear to represent societies that are not that much different economically and socially than what we live in now. However they have semi-miraculous technology that has averted climate breakdown.

For Geostorm all we’ll need is tech to save us [IMAGE: Geostorm]

For us sustainability without greater social justice isn’t really solarpunk.

Some might say that following this logic, what has been described as the first solarpunk novel doesn't deserve that term. New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson shows a society that in many ways resembles the politics and economy of now. In it homeless children live under the landing jetties used by high paid stock brokers to park their pimped-out jetfoils in.

New York, New York it’s a wet and wonderful town [IMAGE: New York 2140 by Kim Stanley Robinson]

We would say that New York 2140 can still be claimed as a solarpunk text. This is because in this partially submerged Manhattan of the future a number of its skyscrapers have been transformed into resident cooperatives.

These mutualised buildings even work with each other to share food, resources and give shelter to those in need. For us this puts New York 2140 just over the line into being solarpunk.

ECO SCI-FI

Many sci-fi writers have explored ecological issues in their stories, from Frank Herbert to David Brin. It could be argued that some eco sci-fi overlaps with solarpunk, most notably Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars Trilogy. We say these are two separate genres.

Elon Musk’s dream come true? [IMAGE: The Mars Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson]

The key difference is that eco sci-fi doesn’t have to show a world that is more sustainable or where humans live in greater harmony with nature. This genre simply explores ecological processes through fiction. It doesn’t necessarily show futures that are more socially just than the present.

Hostile environment, is it a fantasy or our future? [IMAGE: The Broken series by N. K. Jemisin]

A story can explore ecology and society and be in both genres. Just like how our first series are both solarpunk stories and detective thrillers.

HOPEPUNK

Again, this genre can have some overlap with solarpunk, mainly because it shows better futures.

The novels most associated with hopepunk are The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison and Becky Chambers’ books, especially Record of a Spaceborn Few.

Hope amidst the darkness? [IMAGE: The Goblin Emperor by Katherine Addison]

Hopepunk is very much a reaction to the rise of grimdark fantasy, such as Warhammer or the writing of Joe Abercrombie.

In the grim darkness of Warhammer’s far future there is only war [IMAGE: Warhammer 40K]

For us, hopepunk isn’t solarpunk because it doesn’t have to include sustainability and could even be set in a world that has experienced climate devastation. Hopepunk also tends to (but doesn’t always) have more fantasy settings.

Looking to the stars [IMAGE: Record of a Spaceborn Few by Becky Chambers]

Some dispute the existence of hopepunk as a genre at all. Writer and journalist Annalee Newitz said: "Any kind of story can have elements of hopepunk."

It is wide enough to include any story where people are striving for a better world and thus can include anything apart from the most cynical of dystopian stories. Titles as diverse as Harry Potter to Mad Max: Fury Road are listed on the hopepunk Wikipedia page.

As a result of hopepunk’s very broad definition, solarpunk could be considered as fitting underneath its very wide umbrella. We personally don’t feel it's a very helpful term to guide readers, and especially not activists, as something they can cohere around.

SOMETIMES LABELLED AS, BUT NOT REALLY, SOLARPUNK

The SolarPunk Stories sun [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

We want to make clear, just because we think the below aren’t solarpunk doesn’t mean we don’t like them. Our team are big fans of many examples of these genres from The Rings of Power to Robocop.

I’d buy that for a dollar [IMAGE: Robocop by William Tung - Wikimedia Commons]

We just don’t think the examples below are solarpunk and labelling them as such risks confusing those who might want to enjoy this genre more and even join our movement.

It was magnificent, but not solarpunk [IMAGE: Ismael Cruz Córdova in Rings of Power]

FULL BLOWN FANTASY

Worlds with dragons, magic, and elves are not solarpunk for us. Though, we acknowledge that there are some shades of solarpunk set further into the future that use such advanced technology that it allows for more fantastical elements to their stories.

Would you call this solarpunk? [IMAGE: Wikimedia creative commons]

For example the winged creatures in these stories are the product of bio-engineering not supernatural forces.

An exception to this would be a story where the characters believe in supernatural powers but it’s never made clear if these forces actually exist outside of that character's perceptions. Stories like this that leave it ambiguous could still be solarpunk for us like Women of White Water by Helen Kenwright from Solarpunk Summers.

Practical magic [IMAGE: Photo by Almos Bechtold on Unsplash]

The reason why we think this distinction is important goes back to what we think the biggest reason for solarpunk to exist is. It’s for people to not only think ”That looks awesome” but also “We could make it happen. Let’s start building it”. When stories are really magical they become less a call to action and more just an escapist fantasy.

MIYAZAKI FILMS NOT SOLARPUNK

Diesel powered [IMAGE: Castle in the Sky Studio Ghibli]

A number of people have cited Miyazaki’s films, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, Princess Mononoke and Castle in the Sky as examples of solarpunk. We have to respectfully disagree with this.

Magical creatures face off against steam age industry in Princess Mononoke [IMAGE Studio Ghibli - Princess Mononoke]

While a lot of the Kawai Solar visual style seems inspired by Miyazaki’s aesthetic, we think these films aren’t solarpunk. They’d be more accurately described as depictions of alternate pasts, with more that’s fantasy, diesel, or steampunk about them than solar.

A princess protects her peasants against petrol-powered tanks in Castle in the Sky [IMAGE: Castle in the Sky Studio Ghibli]

CYBERPUNK / STEAMPUNK Etc

This shouldn’t need much explaining, suffice to say we see lots of stuff that seems very clearly from this aesthetic labelled as solarpunk for some reason.

OUR HOPE AND A REQUEST

If we can achieve one thing with this piece it’s that when someone says “That’s not solarpunk” a conversation can be had about whether that thing is or isn’t, or is it just one of its shades?

You might think our attempts at definitions are completely wrong or disagree with aspects of them. That’s fine. We are not writing this with the aim of it being the last word.

What shade of solarpunk are you? Cottage vs Metropolis

We’re putting this out there to try and move the conversation forward in a way that encourages a bit more pluralism in the solarpunk scene.

If you do disagree with our definitions we have a request. Instead of (or as well as) attacking us, you consider putting forward your own alternate definitions that you prefer. You never know, we might even agree with you.

DIY shades grid [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]

To help encourage a greater discussion around what the many shades of solarpunk might be we’re making freely available the X/Y axis templates designed by our team mate Claire. These are free for you to use under a creative commons licence.

Argue for Your Shade

While we ask for greater tolerance, or even acceptance, of other people’s shades that doesn’t mean we think you shouldn’t make the case for what types of solarpunk you personally prefer over others.

If you’ve read the SolarPunk Stories Manifesto or the first episode in our SolarPunk Detective series, you’ll see we’re pretty clear on the shades we like and those we’re not so keen on.

Change through Action

At SolarPunk Stories we want to encourage a broader and more diverse movement. One that shares common core values and is inspired to take action with others to make a real difference.

Be a part of the solution [IMAGE Callum Shaw]

One where people of different shades can agree to disagree about things like greened towers, crypto, and even colonising Mars. That, while disagreeing about certain things, we can still come together to build a more deliciously sustainable world.

We hope you’ll join with us to make it so.

Green towers [IMAGE: Stefano Boeri Architetti Eindhoven Trudo Vertical Forest 2018 facade view]

This piece was written by Alex Holland, with contributions by Claire Alexis and Alastair Ball who are all members of the SolarPunk Stories Squad. If you’d like to join our squad and help tell thrilling tales form better futures click here.

If you want to get fortnightly updates on solarpunk style art and activism sign up to our newsletter here.

You can also follow us on Instagram @SolarPunk Stories

WHAT NEXT?

We’re considering organising an event to discuss the ideas raised in this piece. If you’d be up for coming to an event like this, and even speaking on behalf of one of the shades please fill in this form.

![The SolarPunk Stories sun [IMAGE: Claire Alexis for SolarPunk Stories]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cda5a0ec2ff616e812b9450/fd96b247-f28e-4c6f-9999-1f7f6f396a12/SOMETIMES+LABELLED+AS%2C+BUT+NOT+REALLY%2C+SOLARPUNK.jpg)